Don’t Repeat Yourself, Don’t Repeat Yourself

Don’t Repeat Yourself, or as everyone calls it, DRY. It is one of the most known principles in software engineering. Juniors learn it before anything else. They master it so profoundly in their early years that they apply it instantaneously and unconsciously in their later career. But it’s for a good reason. It is a no-brainer, a child’s play. It sticks easily into the heads because of its simple meaning. As it says, reuse your code instead of writing it again. Easy-peasy.

But, like with so many things in life, balance is essential. As Robert Downey Jr. as Kirk Lazarus famously said in the Tropic Thunder movie: “Never go full retard”. I want you to focus on the first “Never go full” part and ignore the last word, which is not my point here. Taking it more seriously, I will show a non-obvious consequence of the overused DRY principle in this article.

I will use an example from the real world since people can think with physical objects more easily than theoretical ones. While it might be arguable initially, our findings will be the same as in software engineering. So, let’s have an automobile factory where we focus on two aspects only.

At first, let’s see how the vehicles get painted. The car assembly plants usually have a centralized paint shop. It’s an absolute singleton reused instance within the entire facility. There are numerous reasons for that. First of all, the vehicles’ colour is business significant. The buyers can choose colours for their dream cars from a wide range. Second, painting is a multistep complex process. It requires an isolated area and extreme cleanliness. It is also highly toxic and flammable. Costs, logistical and other aspects are also there. To sum it up, these reasons, even separately, could already justify why a painting shop is a singleton, shared and reused service within the facility.

The second aspect of our car manufacturing facility is screw driving. We can agree on its necessity and importance in car manufacturing. There are thousands of bolts in a vehicle, and every assembling employee should be able to tighten each perfectly, not force or leave it loose. Does it sound like a BoltTighteningService in our codebase? While you might have such a service in a codebase, there is no such in the automaker industry. Let’s compare it to the painting to figure out why. From a business point of view, it is not relevant. It is a simple process. It does not require isolation or extensive space. Finally, a cheap compressed air impact screwdriver can easily ensure speed and precision. Of course, the facility has such screwdrivers at every assembling stage for all those reasons. While no car would exist without bolts and screwdrivers, it is not a topic. We don’t expose it to the outside world. It is like the air we breathe in every moment. Yet, we don’t talk about it.

These examples provided a good insight into what to consider before extracting and reusing any artefact, whether a car manufacturing process or a piece of code. During coding, we can formulate and ask the same questions we could derive from the above examples. Here are some example questions.

- Is it business-significant functionality?

- Is the functionality meaningful enough in our context to be independent from its usage?

- Does the functionality require publicity and visibility?

- Are the benefits of the extraction greater than the cost of it?

- Is there any technical consideration or limitation that causes the extraction?

If you answer such questions with “no”, you shouldn’t proceed with the extraction and favour a bit of code duplication instead. If you ignore these questions and proceed with the extraction, you will have some downsides. So, let’s look at one of the most significant consequences if we push the DRY principle too far.

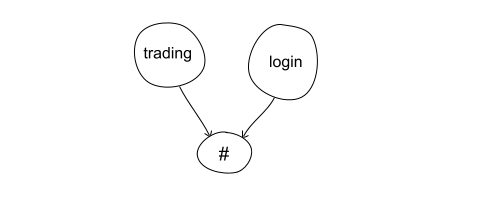

We are switching our car manufacturing example to a trading application we recently started working on. Our application provides only the user interface for the clients. Consequently, we must send all transactions through the network for the trading backend system. We want to avoid any integrity issues during the transmission, so we add a hash value as a checksum to each trading request. So far, so good.

Later in the development, we are switching focus to user authentication. As experienced software engineers, we store only the hashed password in our database, following best practices. Because our product already uses a hashing algorithm for the trading checksums, we decided to reuse that algorithm and, as a DRY zealot developer, our previous implementation as well. To deal with the encapsulation in the trading code, we extract the hashing logic into a new package, module or artefact, and we give it a good name like ChecksumManager. We are ending up with the following structure.

Unquestionably, we reached our goal. No code got duplicated. But what have we sacrificed to achieve it? The most significant side effect, and what this article is primarily about, is that we have connected two utterly irrelevant business functionalities of our code base with a shared dependency. It’s not a substantial dependency, but it’s undoubtedly there and slowly starts to impact us in the future. Whenever we would like to change the checksum algorithm for the tradings, we would affect user authentications, and vice versa. No product owner or business representative would be happy with our work. Returning to the cars for a moment, a tire change on your vehicle should be possible without checking the oil level.

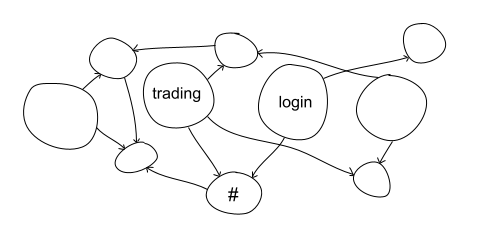

If we walk this path further, more and more such extracted dependencies will arise in our code base, connecting completely irrelevant business functions. After a while, even the extracted codes will start depending on other extracted codes, ultimately heading to the famous spaghetti code.

We must be aware of this consequence when reusing a code piece. We need to consider whether the benefits of code extraction and reuse are more valuable than the cost it implies. This article is not against the DRY. It is a good principle. It is just not enough on its own; we must accompany it with other considerations to have correctly modelled business functionalities, a clear and self-explaining structure and an easy-to-maintain codebase. We must balance and “Never go full”.

On the opposite side, there are aspects where code extraction and reuse is not a question. One of the best examples is the cross-cutting concerns. Logging, security considerations and other similar aspects we must extract and reuse since they can be used all over.

To sum it up, the DRY is a good principle. But consider other software design goals as well. Put all the pros and cons on balance, and if you still make a good deal, go ahead with the extraction and reuse.

Comments